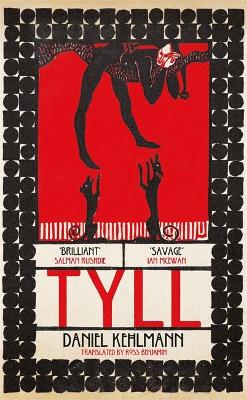

Tyll

By Daniel Kehlmann, and and, Ross Benjamin

avg rating

6 reviews

Buy this book from hive.co.uk to support The Reading Agency and local bookshops at no additional cost to you.

He’s a trickster, a player, a jester.

His handshake’s like a pact with the devil, his smile like a crack in the clouds; he’s watching you now and he’s gone when you turn.

Tyll Ulenspiegel is here!In a village like every other village in Germany, a scrawny boy balances on a rope between two trees.

He’s practising. He practises by the mill, by the blacksmiths; he practises in the forest at night, where the Cold Woman whispers and goblins roam.

When he comes out, he will never be the same. Tyll will escape the ordinary villages. In the mines he will defy death. On the battlefield he will run faster than cannonballs.

In the courts he will trick the heads of state. As a travelling entertainer, his journey will take him across the land and into the heart of a never-ending war. A prince’s doomed acceptance of the Bohemian throne has European armies lurching brutally for dominion and now the Winter King casts a sunless pall.

Between the quests of fat counts, witch-hunters and scheming queens, Tyll dances his mocking fugue; exposing the folly of kings and the wisdom of fools. With macabre humour and moving humanity, Daniel Kehlmann lifts this legend from medieval German folklore and enters him on the stage of the Thirty Years’ War.

When citizens become the playthings of politics and puppetry, Tyll, in his demonic grace and his thirst for freedom, is the very spirit of rebellion – a cork in water, a laugh in the dark, a hero for all time.

TweetResources for this book

Reviews

I thoroughly enjoyed this book despite knowing little about the time period in which it is set. It gradually dawned on me that the prominent characters were based on real people. Rather than use Wikipedia or the like to try to work out who is who, I described them to my daughter who would exclaim "Do you mean Frederick the Great?" (for example). That certainly added to the fun but even if you don't have such a person to help you I recommend the book wholeheartedly. Just don't get too bogged down in fact vs fiction - I find that spoils the fun.

Daniel Kehlmann takes the Thirty Years war (1618-48) – a not very obvious setting for a fantasy novel and imbibes the period with a creative mix of fantasy, playfulness, and huge erudition bringing together figures taken from folklore, and some relatively unknown real life characters. This is historical fiction where the fictional element is given full reign via the eponymous Tyll Eulenspiegel. It’s a fabulous and a multi layered read that employs a non-linear narrative structure appropriate to a story whose influences span centuries.

Kehlmann has a range of different characters and each one is fascinating and unpredictable. Tyll himself is a “trickster”. In a time of itinerant travellers where the road is your guide, we are told “every travelling entertainer was a little bit devil, a little bit animal, and a little bit harmless”. Furthermore, as Tyll declares “When things get tight, I leave”. Is this a loveable personality, or are the sinister elements foremost? Tyll’s relationship with the talking donkey (Origenes) is questionable to say the least; and the roles played by the travellers on this “ship of fools” shift throughout the book. For contemporary British, or American readers, Tyll is rather more The Joker or Jim Carrey than Charlie Chaplin or Puck.

Germanic folklore is embedded in the narrative, but subtly. Grimm’s Bremen Town Musicians sit alongside the lady of the Forest (from Parsifal). An intriguing character is The Cold Woman, forever lurking in the forests and among the willow tree (“the evil tree”). I suspect that Kehlmann’s playfulness extends to the incorporation of very modern references and his German writer peer, Robert Seethaler, may have something to do with the Cold woman.

Tyll himself is the glue that binds the narrative, a sprawling tramp across middle Europe as the chaotic Thirty Years War proceeds. Dynastic ambition is mostly conveyed via the doomed aspiration of Friedrich, Elector Palatine, and more particularly the Princess Elizabeth Stuart, his beleaguered wife. Who is the more ambitious of the two, and who the most determined to regain what is rightfully theirs? That’s open to debate as Kehlmann provides radically different interpretation of events. This is one of the joys of the book- the identification of absolute truth and the competing tendency towards fabrication and falsification. Princess Liz even has a painting whose particular attributes elicit quite different responses from those that see it.

This is very much a character driven novel, and in Athanasius Kircher, Kehlmann has incorporated a gem. Truth is genuinely stranger than fiction in the case of Kircher who was known as the man who knew everything. He is a dragontologist (!) in search of serum to cure the Plague. He is also an expert in Volcanos (perhaps a nod to Alexander Von Humboldt in Kehlmann’s Measuring the World), and a cosmologist, and Egyptologist. Kircher even launched a dragon shaped balloon with the invocation “flee the wrath of God” on the underside- no wonder Kircher was a good choice to take the role of both witch hunter and dragon chaser. Kehlmann introduces these myriad interests with a light touch, all in the context of the real witch hunts which took place in Europe in the pre modern period. Kircher and various assistants and sidekicks (including a great double act with the (sole) Gunpowder Plot escapee, Oswald Tesimond. For his research and inspiration Kehlmann talks glowingly of the John Glassie autobiography of Kircher (“A Man of Misconceptions”), and this is combined with the Hexenhammer (Hammer of Witches) publication of the c. 15th (the century in which the Tyll folklore originated).

The intertextuality of Kehlmann’s writing and his scholarship is impressive. Grimmelshausen’s Simplicissmus (from 1669) is an acknowledged source (and is referred to in Tyll) and the writing of Charles de Coster (the setting being the Dutch Wars of the c. 19 th) is also superbly integrated (mostly via the character of Nele).

In addition to Tyll himself, my favourite character, and the one I returned to for a second read in the fabulous Lord of the Air section, is Claus- Tyll’s own father. Claus is a man with a lot on his mind. He is the embodiment of the religious, philosophical, and magical influences that combined in the middle ages and pre modern period to question, if not challenge, the prevailing order. Heretical thoughts, (heresy in its deviation from the powerful Catholic Church doctrine) occupies Claus and he is a worthy if ultimately unsuccessful challenger to the witch hunters. Claus is the medium through which Kehlmann presents the philosophical/religious debates before the torturer obtains the correct answer. The (omnipotence) paradox of the stone; the paradox of the heap (of sand); Leibniz’s assessment (with Princess’s Liz’s daughter Sophie) of the possibility of two identical leaves, tax Claus. Perhaps most intriguing of all, and integrated seamlessly with the witch hunts, the hangings and the burnings, is Claus’s belief in the power of the grimoire. The grimoire or book of spells is a textbook of magic. Claus carves a pentagram into a tree (Agrippa’s magical symbol); Claus recites the magic squares, the Sator Square and the Milon Square, in the belief this will save him from a painful death. His wife, Agneta, recites the Salom Square, known to help women in labour (at a time when she needs help). Claus calls up the Key of Solomon, another grimoire, while in jail.

I learned a lot about the prevailing dilemmas of orthodoxy promulgated by authority, and the resistance of ancient beliefs coupled with the emerging arguments in the age of reason.

For those readers who love history this is a wide ranging, superbly crafted book. For those who love fiction its pure delight to encounter Kufer, and especially Horridus (as in the Devil’s Club).

I was delighted with a group of Goodreads friends to be selected by the Reading Agency to read this book as part of their shadowing of the International Booker Shortlist.

Overall this in my view by far the most enjoyable on the shortlist.

It has been criticised for being more of a collection of short stories and being too disjointed but I think this is to miss the repeated themes and ideas that recur across the book and make it a coherent whole - and my review explores these.

ALTERNATIVE ACCOUNTS OF THE SAME ISSUE

- Elizabeth and Frederick's first night together (including the petals)

- Wolkenstein's account of his own travels - the real version and the told version (contrasted at length through the whole chapter of his trip to the Battle of Zusmarshausen)

- Elizabeth and Frederick on why he took the throne (this is one with genuine historical resonance)

- Nele and Tyll on who killed the Pirmin (or - a third alternative - was this assisted suicide)

- Through torture Tyll’s father changes his own account and convinces himself he is guilty

- Equivocation (the Porter scene in Macbeth inspired by Tesimond)

GRANDCHILDREN AND THE STORIES YOU TELL THAM

- Martha knows she will tell her grandchildren about Tyll (but she never has them)

- Nela precisely does not tell her grandchildren about knowing and travelling with Tyll

- Wolkenstein tells Elizabeth he will in future tell his grandchildren that he met the Winter Queen

- Wolkenstein does not say the same to (or of) Tyll - although they meet

- Wolkenstein when writing his account 50 years later falsely dramatizes his story to include a child-eating wolf as he is influenced by now having grandchildren

ALTERNATIVE LIVES (OFTEN INVOLVING MARRIAGE)

- Martha wanting to stay in the village, be married and so not fleeing with Tyll - but this future never happening as a result of her choice (after the village is raided)

- Claus contemplating the alternatives of being hung or attempting a magical escape, fleeing and starting anew - and deciding it's a lot simpler to be hung

- Tyll not wanting to be a farmhand and so fleeing his village

- Nele not wanting to marry a Steger son and so fleeing with Tyll

- Tyll and Nele abandoning Gottfried for Pirmin

- Nele not marrying Tyll

- Nele choosing to take the offer of marriage and leave Tyll

- Elizabeth remembering how during the Gunpowder Plot, she fled London (fearing her father dead) to get away from conspirators searching for her to put her on the throne as a puppet Catholic ruler (something she found quite attractive!)

- Elizabeth thinking of her father's plans for her to marry Gustav Adolf (who later humiliates Frederick)

- Elizabeth imagining her older son becoming King at the request of the Parliamentary Party (in fact we know he ends up falling out with the family after - to his and their shock - Elizabeth's brother is executed)

- The Thumbling marrying princess in the story told by Nele as queried by Tyll

- And of course the whole book is a deliberate reworking of Charles de Coster’s ‘The Legend of Thyl Ulenspiegel and Lamme Goedzak” and of Thyl’s relationship there with Nele.

SHAKESPEARE PLAYS

- Midsummer Night's Dream (the donkey head scene)

- Romeo and Juliet (part of Tyll's play in the first chapter and what causes Elizabeth to take Tyll as her fool)

- Macbeth (her father's remarks to Shakespeare on the untested unity of England and Scotland and his fear of witches; Shakespeare's later presentation of the pray - one Elizabeth thought the best she had seen but one she had never seen again, the direct link of Tesimond to the play via the Porter/equivocator scene - https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/the-trial-of-henry-garnet-1606)

- The Tempest (Elizabeth reflects she would never show the same mercy to Wallerstein as Propsero did to his enemies). And of course in the play she watches Shakespeare himself plays the part.

- Hamlet (Elizabeth proud of the way she offers comfort to Shakespeare on the death of Hamnet - a lovely link to a Women's Prize shortlisted book)

DEVELOPMENT OF GERMAN ART

Elizabeth has scathing views on German literature, plays and poetry - partly written tongue in cheek by the author and partly a genuine exploration of its infancy at the time of this book compared to the way in which English art was developing.

Martin Opitz - Elizabeth tries him and finds him unreadable, she later discusses with Wolkenstein and both laugh at the idea of reading him. Wolkenstein sets out his aim to write his life story in German, later we find he does and relies (to describe a battle scene he no longer knows how to describe on an account by another author - Grimmelshausen (see below) - who in turn took his description of a battle he had actually witnessed from a book by an English author who had never seen a battle - translated by, as it happens, Opitz). Note from Peter Wilson's "Europe's Tragedy" (see below) I discovered that the inspiration for Grimmelshausen was Sir Philip Sidney's "Arcadia" - written in 1590 but the 1630s or so German language version of which was edited, indeed, by Opitz.

Paul Fleming - he inspires Wolkenstein (although noted as now dead) - earlier we see him meeting Tyll (and Nele) as part of the dragon chase: before which he discusses his poetry (and writing of it with German) with (a rather baffled at his langague choice) Kircher and Olearius (who reflects that whereas Fleming's poems will soon cease, Kircher's writing will be read for ever)

The book refers to Grimmelshausen’s “The Adventures of Simplicus Simplicussimus” - seen by the Romantics as the first authentic German novel, used by them for their reinterpretation of the conflict (source for both: Europe’s Tragedy: A New History of the Thirty Year’s War” by Peter Wilson” and itself a kind of story of a rogue living through the Thirty Year’s War (so similar in concept to “Tyll”. See also above.

Music - Kircher's role in music is rather downplayed (and only really covered in the context of his - in modern terms) bizarre dragon quest: but his Musurgia Universalis (which is mentioned in the book) was actually what lead to his indirect immortality as it inspired Bach, Beethoven and Handel.

LINKS TO OTHER BOOKS

Adam Olearius is described as (and historically was) a mathematician and a geographer. Is this a nod to “Measuring the World” which of course was about two characters: a Geographer and a Mathematician.

MISSING CHILDREN OF SOPHIE (MY ONE CRITICISM!)

- Price Rupert: As an English reader its disappointing that one of the most fascinating characters of the Civil War/Inter-regnum/Restoration years is not (as far as I can tell) mentioned in the book at all. I kept hoping to spot him but unlike his two older brothers he does not make it. And this character is relevant to the story - Frederick's naming of his son (born just after the fateful decision to accept the Bohemian Crown which dominates the book) after the only emperor of the Palatine dynasty, was as a crucial sign of his dynastic ambition.

- Sophie of Hannover: And perhaps even more disappointing to see no mention of Rupert's sister - her name still fundamental to our entire Hereditary system via the Act of Succession.

My only previous experience of Kehlmann was [book:Measuring the World|642231], which I read too long ago to remember clearly. This one is a very different sort of historical novel. It mixes the picaresque and the fantastic with unsparing descriptions of the harshness of 17th century life, and the savage effects of the Thirty Years War on Germany. It also mixes fact and fiction in a way that can be hard to disentangle

The book is episodic, with the episodes linked by the legendary trickster Tyll Ulenspiegel, an entertainer, juggler and tightrope walker. The episodes are not arranged chronologically - the first is a vivid account of the appearance of his travelling band in a poor village, but the next describes his childhood, and the process that led to his father's execution for witchcraft. Later we see him as the fool of the exiled King of Bohemia Friedrich, the "Winter King" and his queen Liz, daughter of the British king James I (and VI).

There is plenty of unreliable narration, and plenty of period detail, and some of the more eccentric beliefs of the period are very entertaining. Definitely worth reading, and I might have given it 5 stars had it been a little less disjointed and uneven.

The book is in 8 chapters, which are of very different lengths - varying from 16 pages to 110 in the UK hardback edition. Taking these in order:

(1) Shoes (p3)

This introductory chapter is set in an unnamed village which has not yet been affected by the Thirty Years War. A villager narrates the tale of what happens when Tyll Ulenspiegl and his troupe visit the village in a wagon, which they turn into a stage. It introduces many of the recurring themes of the book, for example the play they perform is about the winter king, we meet the talking donkey for the first time and witness some of the key acts in the performance. We also meet Nele, who Tyll describes as a sister but not my sister. Tyll is a juggler, tightrope walker, illusionist and practical joker - the practical joke involves getting the villagers each to throw a shoe up in the air, which creates havoc when they try to retrieve them. At the end of the chapter we hear that the war reached the village a year later and almost everyone there was killed.

(2) Lord of the Air (p21)

In this long and pivotal chapter we travel back to Tyll's childhood. His parents Claus and Agneta run a mill which they inherited from Agneta's father, but Claus also dabbles in magic. The young Tyll is seen practicing tightrope walking and juggling, and being bullied by the mill hand Sepp. A heavily pregnant Agneta, Tyll and another mill worker Heiner take a donkey cart across the forest to deliver some flour, but on the way Agneta goes into labour, and she and Heiner return to the mill leaving Tyll in a clearing guarding the precious sacks of flour. Tyll hears something approaching and goes into a fever. Claus returns the next morning and finds a scene of destruction - the sacks are open and there is flour everywhere, and the donkey has been decapitated. They find Tyll naked in a tree, covered in flour and wearing part of the donkey's head. A stranger comes to town - he turns out to be an imagined version of a real historical figure Athanasius Kircher, who is working as a witch hunter with Tesimond, another real person. Kircher expounds some of his strange theories and asks Claus about a book he has. Claus is tried and convicted of witchcraft, and Tyll leaves the village with the baker's daughter Nele to join Gottfried, a travelling balladeer.

(3) Zusmarshausen (p131)

This chapter tells the story of "the fat count" Martin van Wolkenstein, who has been travelling across war-ravaged Germany in search of an abbey where Tyll is believed to be, on a mission to bring Tyll to the Kaiser. Tyll agrees to go with him, and they stumble across the final major battle of the War.

(4) Kings in Winter (p165)

We travel back again, and meet the royal couple, Friedrich, the Winter King and Elizabeth Stuart, or Liz. They recount the story of their marriage, and how Friedrich came to accept the Bohemian throne - Tesimond is mentioned in passing as an English Jesuit. They have a fool, who turns out to be Tyll, accompanied by Nele. He gains Liz's favour by exhibiting a blank canvas, claiming it can only be appreciated by the stupid, the deceitful and the illegitimate. Nele tells Liz some of her history, and says that Tyll killed one of their early leaders, Pirmin. Friedrich takes Tyll on a journey to meet the powerful Swedish king Gustav Adolf. After this meeting their party travels through the snow, where Friedrich shows signs of the plague and is left to die in the snow. Tyll travels on.

(5) Hunger (p235)

This short section is set early in Tyll's career, as he and Nele are learning their trade as performers with the harsh and mean Pirmin

(6) The Great Art of Light and Shadow (p251)

We return to the story of Kircher, who is talking to Olearius, the Gottorf court mathematician, about a cure for the plague, which requires the blood of the last living dragon. They meet Fleming (another real figure) who tells them he is writing poems in German. They encounter a travelling circus and meet Tyll, who walks a tightrope and demonstrates his talking donkey. Nele describes their life as jesters to the winter king. Tyll persuades her to marry Olearius. At the end of the chapter the death of the last dragon is briefly described.

(7) In the Shaft (p287)

In this chapter Tyll is one of a group of men trapped in a mine shaft in Brno, which is under siege by the Swedish army. The situation appears hopeless but Tyll declares that he will not die there.

(8) Westphalia (p309)

In the final chapter we return to the widowed Liz, who has left her home in The Hague, travelling to a diplomatic congress in Osnabruck to plead her case with the Kaiser's Ambassador on behalf of her son. She manages a meeting by sheer will-power and bearing. She meets a Count Wolkenstein, who tells her about Fleming's German poems. She then visits the Swedish ambassador. She attends a reception where she meets Tyll, now a musician, who tells her of Nele's marriage and disappears.

"They cannot kill him. He will also escape."

Having read all 13 of the International Booker longlist prior to the shortlist, I was a little surprised to see this book make the cut. An enjoyable read but rather less ambitious in literary terms than the other 5 novels.

Tyll by Daniel Kehlmann has been translated under the same title by Ross Benjamin.

I have previously read his Measuring the World, translated by Carol Brown Janeway and Fame: A Novel in Nine Episodes translated by Carol Brown Janeway and George Newbern.

Tyll is based around the eponymous trickster (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Till_Eulenspiegel) but he is relocated to the time of the Thirty Years War. This paper http://orca.cf.ac.uk/125217/1/16.pdf provides a good overview of how Kehlmann's Tyll fits in with other literary versions including Charles de Coster's book The Legend of the Glorious Adventures of Tyl Ulenspiegel in the Land of Flanders & Elsewhere, which also relocated Tyll to a similarish timeframe.

The novel starts wonderfully, in the midst of the conflict, with a piece that actually constitutes a self-contained short story, available here: https://bombmagazine.org/articles/shoes/

"The war had not yet come to us. We lived in fear and hope and tried not to draw God’s wrath down upon our securely walled town, with its hundred and five houses and the church and the cemetery, where our ancestors waited for the Day of Resurrection.

We prayed often to keep the war away. We prayed to the Almighty and to the kind Virgin, we prayed to the Lady of the Forest and to the Little People of Midnight, to Saint Gerwin, to Peter the Gatekeeper, to John the Evangelist, and to be safe we also prayed to Old Mela, who during the Twelve Nights, when the demons are let loose, roams the heavens at the head of her retinue. We prayed to the Horned Ones of ancient days and to Bishop Martin, who shared his cloak with the beggar when the latter was freezing, so that they were then both freezing and both pleasing to God, for what’s the use of half a cloak in winter, and of course we prayed to Saint Maurice, who had chosen death with a whole legion rather than betray his faith in the one just God."

and then Tyll arrives:

"Leaflets came even to us. They came through the forest, the wind carried them, merchants brought them—out in the world more of them were printed than anyone could count. They were about the Ship of Fools and the great priestly folly and the evil Pope in Rome and the devilish Martinus Luther of Wittenberg and the sorcerer Horridus and Doctor Faust and the hero Gawain of the Round Table and indeed about him, Tyll Ulenspiegel, who had now come to us himself. We knew his pied jerkin, we knew the battered hood and the calfskin cloak, we knew the gaunt face, the small eyes, the hollow cheeks, and the buckteeth. His breeches were made of good material, his shoes of fine leather, but his hands were a thief’s or scribe’s hands, which had never done work; his right held the reins, his left the whip. His eyes flashed, he greeted this person and that."

and proceeds to cause chaos, while teaching the villagers a valuable lesson in to the bargain.

The rest of the novel failed to live up to this strong start for me. The story then explains Tyll's origins, and then follows him, in a decidely non-linear fashion, through a picaresque based around the Thirty Years War.

But having created such a memorable main character in Tyll, Kehlmann often loses sight of him, and the novel flags when he isn't on the page.

I also felt it wasn't clear if the author wanted us to think of, and sympathise, with Tyll as a fully human character, or as more an agent of chaos (personally I rather preferred him as the latter).

That said, this latter point, is an illustration of what the novel does very well: effectively portraying 'pre-modern' times, after the loss of faith in religious authorities but before the enlightenment, with their odd blend of science and superstition, and with no real attempt to distinguish between the two. This is neatly encapsulated in the fictionalised version of the real-life figure of Athanasius Kircher, and also in the way that the book may, or may not (depending on the reader's interpretation) feature dragons and a talking donkey.

In this fascinating Youtube video (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=47Tf3H6aXR8) Kehlmann explains some of the key differences to our modern times. But watching the video pre-reading perhaps marred my experience, as the middle-parts of the novel felt at times like box-ticking for each of these items (water is contaminated and milk expensive so many drank beer and so were permanently intoxicated; high infant mortality must have meant parents would be less emotionally attached to their children; many never left their place of birth; fear was a constant particularly the fear of pain; most suffered constant hunger; diplomacy involved elaborate rules of conduct; the role of the jester was to speak truth to power). Further many of these observations are based on a rather simplistic view of history.

I prefer my historical fiction when it has contemporary relevance - and there were some interesting, if possibly unintentional echoes, here. The people in the opening chapter, waiting for the war, causing devastation elsewhere, to reach them feels rather like the current Covid-19 situation (which clearly wasn't in the authors mind when he wrote the book - indeed to the contrary in interviews he has tended to talk about the wonders of modern medical science mean that fear of disease has been banished). And I was struck how in those times, when there was little freedom of expression, the role of the jester, such as Tyll, was to speak truth unto power. Now when there is, or rather was, a mainstream consensus on liberalism (c.f. Fukuyama) the populist jester actually seeks and sometimes achieves election to high office.

In the novel's weaker middle sections, characters e.g. Shakespeare appeared to be wheeled on simply to tick more boxes. Although the best fleshed-out supporting character was 'the Winter Queen' Elizabeth Stuart (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elizabeth_Stuart,_Queen_of_Bohemia) and the novel ends on an effectively poignant note with the diplomacy that ended the conflict.

Overall a good longlist choice and an enjoyable read generally, but not shortlist material.

I read this book twice in the period of a couple of months. My first reading was somewhat hurried: it was part of my reading of the longlist for the Booker International prize. My second reading was far more considered: a book club of which I am a member was selected to be part of a read along shadowing the main jury and we were given this book to discuss together.

After my first reading, I wrote a short review that ended with a resolution to re-read the book, so the prompt for a re-read was welcome. It’s a book that repays a second, careful read.

Kehlmann has lifted the character of Tyll Ulenspiegel out of 14th century German folklore and dropped him into the 17th century in the time leading up and through the Thirty Years War. This is just one of the things Kehlmann does that shows us that historical accuracy is not at the top of his list of priorities (see also his use of the words “dracontology” and “crystallography” - I don’t know for sure, but a quick Internet search suggests these words originated in the 20th century). My knowledge of 17th century history is very limited, but I am sure any reader with a working knowledge of the period will come away with a long list of anachronisms, contradiction and errors. It is my belief that all of these are deliberate.

The story we read is presented non-chronologically. We begin with Tyll as a young man creating havoc in a village just before the war arrives there. There is a comedic scene where he tells all the villagers to take off and throw their shoes and then to collect them and the arguments that ensue run far more deeply than whose shoe is whose. It’s funny, but it shows a more serious side to Tyll in the way he can uncover, or expose, what lies beneath the surface (he does this again, notably, later on in a royal court where he presents a black piece of paper as a painting which only high-born, educated people can see: the ramifications of people trying to work out how to respond to the picture in the presence of the king and queen rumble on for many pages). This idea of Tyll exposing hypocrisy is one of the key ideas in the novel.

Then we skip back to Tyll’s formative years when he learned his entertainment skills but also when, probably more importantly, his father was tried for witchcraft by two traveling Jesuits. This introduces a key theme of the novel which is the bizarre logic that leads to:

”The accused confessed.”

“But evidently under torture?”

“Yes, of course,” cries Dr. Tesimond. “Why else should he have confessed? Without torture no one would ever confess anything!”

Tesimond sees no contradiction or problem with what he is saying and this happens again and again. There is also more odd logic around beliefs in supernatural powers:

“But how do we know that dragons exist?” asks the boy. Dr. Tesimond furrows his brow. Claus leans forward and slaps his son’s face. “Because of the efficacy of the substitutes,” says Dr. Kircher. “How would such a puny insect as the grub have healing power if not by its resemblance to the dragon! Why can cinnabar heal, if not because it is dark red like dragon blood!”

And the book has several unexplained inconsistencies that are, I believe, completely deliberate. One person remembers 3 petals in an incident whereas the other party remembers 5. Nele says Tyll killed someone whereas Tyll says it was Nele who did it. The Guardian refers to the different episodes as ”slyly contradictory” which seems a great way to sum it up.

Then we skip forward to the final battle of the Thirty Years War, back a bit to the middle of the war, back further to not long after the trial of Tyll’s father, forward to the middle of the war again (just a bit later than where we were last time we were here), forward to almost the end of the war and finally to the negotiations that brought the war to a close.

Tyll is in and out of the story, but never far away. He is less of a “main character” and more of a “connecting thread”. Tyll makes people take a look at themselves, he uncovers hypocrisy. And hypocrisy is a key theme in the novel. We see it in the logic of the Jesuits persecuting magic but wilfully ignoring their own superstitions and magical beliefs (the way they rationalise all this will, quite possibly, make your blood boil). We see it in the attitudes of the royal or governmental courts as individuals battle for position.

The New Yorker puts it like this (the opening statement refers to a character’s obsession with hieroglyphs: in another display of bizarre logic, he believes he has decoded them and then assumes that when some are found that don’t fit his code it is because the author of the originals made mistakes):

"The subtlety here lies not just in the rampantly erroneous Christianizing of a pre-Christian world but in the way these two religious languages, a supposedly pagan Egyptian religion and the certainties of European Christianity, are forced to judge each other, insisting as they do on their shared magic.

Thus Kehlmann’s decision to set his novel in a time of religious conflict gradually reveals its rationale. The Thirty Years’ War was a seismic reordering of European power produced by the earlier upheavals of the Reformation. The Holy Roman Empire comprised largely Protestant northern states and largely Catholic southern states. When Ferdinand II, the devoutly Catholic emperor, attempted to impose religious uniformity, the fragile coalition broke apart, and the policing of piety became brutal. García Márquez’s magic realism flourishes and expands within the relaxed folk Catholicism of Macondo; in the world of “Tyll,” narrow-minded religious and civil authorities seek to control the very definition of the magical."

It is fascinating to read in the New York Times about Kehlmann’s experiences while writing this novel.

“'Tyll' took him five years to write, twice as long as any of his other novels. Kehlmann was about two-thirds of the way through when Donald Trump was elected president in 2016. Kehlmann, his wife, the human-rights lawyer Anne Rubesame, and their son, Oscar, live in Manhattan, after years shuttling between New York and Berlin.

'When Trump won, I was so shocked and worried that for a while I couldn’t write anymore,' Kehlmann says. 'But then I thought of Tyll’s resilience and his way of making fun of anything. It was revelatory because I’d never had any experience of my own character helping me to finish something or to cope.'"

And it is certainly the case that, without know this, I underlined several speeches by two characters in this book with a comment “Trump inspired?”.

And the NYT goes on to say:

“His fascination for comic writing is very unusual in German literature nowadays, especially the way he combines it with elements of horror,” says Alexander Fest, Kehlmann’s longtime editor at his German publisher Rowohlt Verlag. “I think he grew fascinated by Tyll Ulenspiegel because two of the things he’s interested in came together in this one character. Tyll is an uncanny figure in the way he makes fun of people and is funny — not for the people he makes fun of, but for the others standing around.”

And all this just scratches at the surface of this cleverly constructed novel. I thoroughly recommend reading it twice, maybe more than that: it is one of those novels that reveals more the more you look at it.