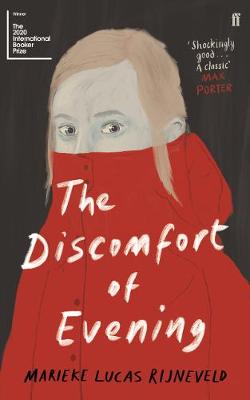

The Discomfort of Evening

By Marieke Lucas Rijneveld

avg rating

6 reviews

Buy this book from hive.co.uk to support The Reading Agency and local bookshops at no additional cost to you.

I asked God if he please couldn’t take my brother Matthies instead of my rabbit. ‘Amen.’ Ten-year-old Jas has a unique way of experiencing her universe: the feeling of udder ointment on her skin as protection against harsh winters; the texture of green warts, like capers, on migrating toads; the sound of ‘blush words’ that aren’t in the Bible.

But when a tragic accident ruptures the family, her curiosity warps into a vortex of increasingly disturbing fantasies – unlocking a darkness that threatens to derail them all. A bestselling sensation in the Netherlands, Marieke Lucas Rijneveld’s radical debut novel is studded with images of wild, violent beauty: a world of language unlike any other.

TweetResources for this book

Reviews

The Discomfort of Evening is indeed an uncomfortable story and not for the faint hearted but if you're up to it it's a gripping read. It's grim and claustrophobic but told with a dark humour that makes it bearable. The reader experiences the curiosity and distress of an emotionally disturbed adolescent living in a disintegrating family following a terrible tragedy. It's brilliantly translated from Dutch by Michele Hutchison.

This is a novel about the effect of the death of a brother through a tragic accident on his family as experienced by his young sister, the narrator. Her childish, imaginative mind struggles to make sense of death and the behaviour of her parents and siblings and she devises her own irrational, logic to explain and attempt to influence events. The life of the family is dominated by farming, farm animals and the fundamental religion they follow, secluded from modern, mainstream society. In their grief the parents are no longer available to their 3 surviving children who experiment in dark sexual and morbid activities. This novel achieves its purpose to engender discomfort in the reader as we are told discomfort is good as in discomfort we are real. The author's remarkable use of imagery and metaphor takes the reader closer to the reality of the narrator.

A thoroughly disturbing book which I simply could not get to grips with. I found it utterly depressing and it was a chore to finish it (which I didn’t). Perhaps after lockdown has finished and my sanity has returned, I may try and finish it but I’m certainly in no hurry.

The discomfort of evening was a sad but also infuriating read. It was clearly based on the authors own childhood but it was hard to believe that this story had been set in the year 2000 as it could just have easily been set in the 1950s with the descriptions of the family’s life on the farm. The book does reflect rural life, particularly in areas cut off from large towns, where traditions remain strong.

The book has been written in, my opinion, Dutch literary style. Over complicated sentences to make the reader feel they are ready something worthy and not just reading for pleasure. It’s possible that I may have enjoyed it more if I’d read it in the original language but I doubt it.

If my book club had not chosen to read this I would not have finished it.

“Death announces itself in most cases, but we’re often the ones who don’t want to see or hear it. We knew that the ice was too weak in some places, and we knew the foot-and-mouth wouldn’t skip our village."

Perhaps my favourite book from the International Booker longlist, having read all 13.

De avond is ongemak was a bestselling debut novel by Marieke Lucas Rijneveld, published when they were 26, and has been translated from the Dutch as The Discomfort of Evening by Michele Hutchison.

The novel is begins just before Christmas 2000 and is narrated by Jas who begins the novel:

"I was ten and stopped taking off my coat. That morning, Mum had covered us one by one in udder ointment to protect us from the cold."

She lives with her parents, her older brothers Matthies and Obbe and her younger sister Hanna on the family diary farm:

“No one stood a chance against the cows anyway; they were always more important.”

She is worried her father is fattening up her pet rabbit Dieuwertje (“I’d named him after the curly-haired female presenter on children’s TV because I found her so pretty.” - that being Dieuwertje Blok, who rather marvellously, narrated the Dutch audiobook https://twitter.com/mariek1991/status/981457382223081474).

And Matthies is “going on ahead to the lake where he was going to take part in the local skating competition with a couple of his friends. It was a twenty-mile route, and the winner got a plate of stewed udders with mustard and a gold medal with the year 2000 on it”, but when she asks to come with him he refuses “and then more quietly so that only I could hear it, ‘Because we’re going to the other side.’ ‘I want to go to the other side, too,’ I whispered. ‘I’ll take you with me when you’re older.’”

As he leaves Jas ponders:”I thought about being too small for so much, but that no one told you when you were big enough, how many centimetres on the door-post that was, and I asked God if He please couldn’t take my brother Matthies instead of my rabbit. ‘Amen. “

Matthies is indeed taken – the local vet comes to break the news that, skating where he shouldn’t, Matthies fell through the ice and drowned, and the family is devastated. Her parents retreat into silence, Jas can’t quite comprehend his death

The cancelling of the family festivities and taking down of the Christmas tree strikes her more than the news: “It was only then that I felt a stab in my chest, more than at the vet’s news. Matthies was sure to return but the Christmas tree wouldn’t.”. And her denial includes refusing to take off her coat, which she wears continuously for months, and self-imposed severe constipation: “I could hold in my poo. I wouldn’t have to lose anything I wanted to keep from now on.”

These events have echoes of the authors own life, except they were only three when their brother died in a car accident:

"Mijn eigen broer Arjen was twaalf toen hij verongelukte. Ik was net drie en ik begreep niet hoe hij ineens zomaar weg was. Alles werd meteen anders. Er werd amper over zijn dood gepraat en mijn ouders haalden onmiddellijk de kerstboom weg. Kinderen snappen dat niet; zodra je zo’n boom verwijdert, wordt het nóg nadrukkelijker dat er iets ergs aan de hand is.

My own brother Arjen was twelve when he died in an accident. I was just three years old and I didn't understand how he suddenly disappeared. Everything immediately changed. There was hardly any mention of his death and my parents immediately removed the Christmas tree. Children don't understand that; as soon as you remove such a tree, it becomes even more emphatic that something bad is going on."

(From https://www.ad.nl/utrecht/als-ik-schrijf-weet-ik-wie-ik-ben~aa4f625c/ - Google translation)

Marieke Lucas Rijneveld was previously known as a poet, and has explained in interviews (https://www.volkskrant.nl/cultuur-media/me-alleen-lucas-noemen-zou-ik-een-te-grote-stap-vinden-maar-ik-word-nooit-meer-alleen-marieke~b62d2ce7/) how, in their view, the move to prose required them to both master dialogue, but also introduce more scatological elements (“Maar in een roman moet er af en toe ook gewoon iemand even gaan poepen of een boterham met kaas eten” = “But in a novel, now and then someone just has to poop or eat a cheese sandwich”), and cites as her inspiration the novelist Jan Wolkers, who is also quoted in the epigraph (“Hij schreef wat hij wilde schrijven, over seks, het geloof, over alles” = “He wrote what he wanted to write about sex, faith, about everything.”)

Faith plays a key role – Jas’s parents, as the authors own, are members of the Reformed Church. Her own relationship with God is complicated, but her language, and that of the novel, is inflected with scripture: “I’ve got so many words but it’s as if fewer and fewer come out of me, while the biblical vocabulary in my head is pretty much bursting at the seams. “

Jas’s upbringing is strict. The television is hidden away in a cabinet as something shameful and even when watched the content is controlled, and ideally confined to the wholesome Dieuwertje Blok:

“We didn’t have any of the commercial channels, only Nederland 1, 2 and 3. Dad said there wasn’t any nudity on them. He pronounced the word ‘nudity’ as though a fruit fly had just flown into his mouth–he spat as he said it.”

Popular music is generally frowned upon, although an exception is made for Boudewijn de Groot, even her mother unable to avoid joining in with Land van Maas en Waal: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iOKwT8D6XmY

And the death of their son only causes her parents to retreat further “everything that requires secrecy here is accepted in silence”, leaving the children to learn the facts of life themselves and to experiment with violence and sexual feelings, and the imaginative Jas to fantasise about the mysterious ‘other side’ of the lake and (bizarrely) that her mother has hidden some refugees from Hitler (whose birthday Jas shares) in the cellar:

“Anything can happen, I think then, but nothing can be prevented. The plan about death and a rescuer, Mum and Dad who don’t lie on top of each other any more, Obbe who is growing out of his clothes faster than Mum can learn the washing labels off by heart, and the way not just his body is growing but also his cruelty; the ticking insects in my belly which make me rock on top of my teddy bear and get out of bed exhausted, or why we don’t have crunchy peanut butter any more, why the sweets tin has grown a mouth with Mum’s voice in it that says, ‘Are you sure you want to do that?’ or why Dad’s arm has become like a traffic barrier: it descends on you whether you wait your turn or not; or the Jewish people in the basement that no one talks about, just like Matthies. Are they still alive? “

And as the novel progresses into 2001, further tragedy strikes, as foot and mouth disease spreads from the UK to the Netherlands. The quote that opens by review feels particularly chilling read in February 2020 as Covid-19 spreads around the world.

Highly recommended and a contender to win the overall prize. Thanks to the publisher via Netgalley for the ARC.

An English-language interview with the author:

https://www.dazeddigital.com/life-culture/article/48140/1/marieke-lucas-rijneveld-interview-the-discomfort-of-evening

Perhaps not the uplifting read I needed at this challenging time of lockdown although undoubtedly this is a memorable if disturbing read which left me throughly depressed.At times I felt uncomfortable ready it and wondered what more shocking images and incidents the author might present me with.

The first third of the book was I felt an excellent portrayal of the perceptions of a child experiencing life on a Dutch smallholding where 10 year old Jas lives with her strict Reform Church family consisting of her parents and her 3 siblings. The author portrays life through a child's eye view with all its misunderstandings and the imagery focussing on food, animals (particularly cows, toads, and rabbits) , and smells. Tragedy hits with the drowning of the eldest child Matthies on the ice at Christmas and our narrator Jas blames herself for his death as she wished him dead rather than her rabbit.

The second half opens 18 months later with subtle changes in the way in which Jas talks revealing how the family have been traumatised by grief and the ways in which each one of them copes with it. Clearly all of them are suffering from psychological damage. The children self harm, the mother is depressed, does not eat and manifests manic behaviour, and the father becomes increasingly aggressive. The children are essentially ignored and neglected. Jas is desperate for warmth, love and physical contact but the family do not talk and never mention the death but turn in on themselves and their religious beliefs. Jas displays her fear of her parents dying too by having stomach aches and constipation and insists on wearing a red coat constantly as some kind of protection.The children turn to each other and their few school friends for support . There are endless scatalogical references, and the tone is claustrophobic, bleak and depressing.

The third section however descends into relentless, repetitive and at times violent, shocking incidents of sexual exploration, animal torture and cruelty which are disturbing, depressing and distressing. The focus on animal and bodily excretions, the brutality of life on the farm particularly after it is hit by Foot and Mouth disease, are no doubt accurate but I wonder if perhaps at times the author was trying to shock with each progressively explicit incident.

Difficult to know if this is a likely winner and I think opinion will be divided with many people choosing not to finish the book I suspect. The writer is a poet and this is her debut novel I gather. There are poetic elements in the writing and her child's eye view of the world is well drawn - I hope not all from her own experiences though.